Can low-Dose Cannabis Induce Ergogenesis in Highly Skilled Athletes Evidencing Signs of Tolerance to the Effects of Regular Cannabis Use?

By Ally (aka pflover)

“Preserve Neuroplasticity!”

This last April a mixed martial arts (MMA) fighter by the name of Nick Diaz was asked about his use of cannabis in a prefight interview. The Times quoted him as replying “I’m more consistent about everything being a cannabis user.” This was followed up by “And I have an easy way to deal with [being tested]. I can pass a drug test in eight days with herbal cleansers. I drink 10 pounds of water and sweat out 10 pounds of water every day. I’ll be fine (1).” Sure enough he passed the post-game drug test later that month (2).

Nick has not always passed in the past however. At least two different state commissions have caught him testing positive for cannabis when he did not expect to be tested. First, in 2007, while fighting for the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) Mr. Diaz had a win over Japan’s Takanori Gomi revoked after testing positive for THC because it was claimed his levels were so high he must be numbed to the pain. This effect is considered ergogenic, something which improves performance as it relates to sports or physical activity. He tested positive again in his first post-UFC fight (2).

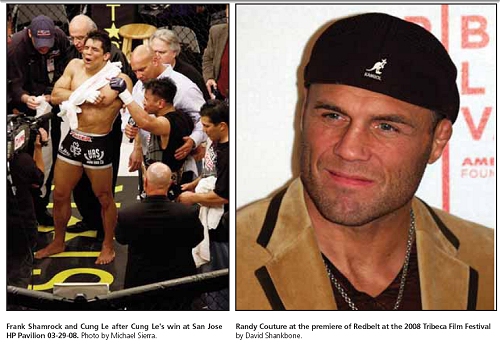

Preferring Nick keep his private life private, neither his coach nor his opponent approved of Diaz’s candor about his “lifestyle choices,” but for different reasons. When asked about his opponent’s comments, Frank Shamrock, a veteran MMA fighter, said: “He definitely smokes marijuana. That’s his own business, but it’s not the greatest thing for the sport. We’re fighting a stigma. Still, there’s something refreshing about his honesty… I respect his talent, he brings it (1).” “But I certainly don’t agree with his lifestyle and his marketing of that lifestyle as a part of mixed martial arts, because I don’t think that’s a part of the sport. I think he’s somewhat of a freak in that way (2).”

Although not appearing to care about the use of cannabis itself, Cesar Gracie, Nick’s coach and long time mentor, has repeatedly asked Nick to stop being so open about his cannabis use, saying “Smoke weed all you want —legally in California, you’re allowed to. Just stop talking about it.” Gracie wishes he could get it through Nick’s head. “I want him to be known for his skills, not his drugs. He doesn’t need to be the spokesperson for cannabis (3).” (I for one commend Mr. Diaz for his integrity.)

Nick Diaz is not just a recreational cannabis user. The Stockton resident is prescribed cannabis under California’s Prop 215 to help manage the symptoms of his ADHD (1). As he says, it makes him more consistent. Apparently Nick has tried to oblige his coach’s request in the past, but one characteristic of those with ADHD like Nick and myself is that we tend to be open books — ask us anything and we spill it, so to speak. It tends to make for a very poor poker face (3).

You might be wondering at this point, “Why is cannabis a prohibited substance by the California State Athletes Commission, considering Prop 215?” The answer is not clear, but it seems likely they agree with the Nevada SAC when they revoked his win over Takanori Gomi, in stating that “the drug is banned because of the damage it does to the person taking it. It could make you lethargic, slow your reflexes, and those are dangerous things in a combat sport (1).” This, of course, leads to another question: what does Mr Diaz’s record look like? The 26 year old is in fact a champion fighter, having held multiple titles in his weight class. Technically he has won 75% of his 28 professional fights, however, officially it is 71% because of the No Contest ruling in the fight against Takanori Gomi (4). For comparison, The Shamrock, Diaz’s most recent opponent and another multi-title Champion, has only won 66% of his 35 professional fights (5) and Randy Couture, also a multiple title holding UFC Champion, has only won 64% of is 25 professional fights (6). Clearly, Mr. Diaz is doing something right, but maybe he is just a fluke in the system and of no real significance to the bigger picture.

I had my suspicions, however, that he was not just a fluke and decide to investigate the effects of cannabis use on performance. I focused my research in six different areas: the official word on cannabis as a doping agent in sports, performance in driving, performance in general in novice vs. regular users on several measures, performance in other athletes known to use cannabis and how they feel about it, how this relates to the psychological state of flow known colloquially as being “in the zone” or “in the groove,” and finally, the evidence the state that regular cannabis use produces should facilitate getting into this zone and what this should mean to the novice versus skilled athlete.

Cannabis Doping: The official Word

In 1998, Ewing published an investigation into differential use of cannabis in athlete vs. non-athlete high school students. Interestingly, he found that cannabis use was higher among the male athlete population than in the non-athlete males. The reverse was true for female athletes. Ewing suggested that this might be due to a delayed first exposure effect in this group who were more likely than their non-athlete counterparts to forgo trying cannabis until after high school (7). In 2005, a similar study was published on French Sports Science University students which suggested both what might be possibly motivating this use and whether or not it had an enhancing or deleterious effect on the athletes. The authors suggested that cannabis was used to enhance performance via the relaxing qualities it produces. Furthermore, reported cannabis use for this reason was positively correlated to the competitive intensity of the sport in question (8). This is the closest contemporary science appears to have come to observing or recognizing this potential for cannabis to play a beneficial roll in an athlete’s overall plan or, depending on one’s perspective, to act as an effective doping agent.

Most available attempts in the literature to address the topic of cannabis use by athletes have been quite firmly against it. Although most acknowledge that cannabis is used by athletes for its relaxing effects they claim this is not enough to account for a performance enhancing effect considering all the other effects of cannabis. Often these studies focus on the immediate effects of acute cannabis intoxication such as impaired explicit and spatial memory functions, impaired focused attention on complex tasks, impaired sustained attention, impaired balance, reduced psychomotor activity, reductions in total cardio output and resulting reduced stamina for sustained activity (9, 10, 11). Indeed, this appears to be the end of the mainstream scientific party line with no attempt to dig deeper to elucidate why so many athletes choose to use cannabis (see Table 1) or what it might be doing for some of the more skilled individuals among them.

Cannabis and Driving: Performance in a Complex Behavior

Performance of skilled athletes, who regularly use cannabis, especially at various times following administration, has not particularly been studied yet. That said, many researchers use the evidence provided by studies on the effects of cannabis intoxication on driving performance for an example of a reasonably well-learned complex behavior requiring many functions required by sports minus the physical exertion (I suggest this simple difference matters, more on this later). I shall do the same while attempting to point out some of the issues with this analogy as it pertains to skilled athletes.

In drivers apparently novice to, or at least not significantly familiar with, the effects of cannabis, THC was orally administered via either 20mg Marinol or 16.5mg /45.7mg THC hemp milk drinks. Blood samples were taken at various intervals following administration to track serum levels of THC, its active metabolite 11-HO-THC, and their inactive carboxylated metabolite 11-nor-9-COOH-THC. This was accompanied by tests of skills necessary for safe driving. Subjects were also asked how willing they were to drive in several situations of varying degrees of perceived importance. Peak serum levels of THC were reached within an hour but peak intoxication correlated better with the peak in the ratio of (THC + 11-HO-THC):11-nor-9-COOH-THC. This is also when the strongest impairments on the tests of driving related skills, such as tracking, were observed and when subjects were least willing to drive, reporting the effects of intoxication to be unpleasant at the highest dose. Even so, many subjects were still willing to drive in the situations with the highest perceived importance (12).

The subjects in this study do not appear to be regular users of cannabis or may even be novice to its effects. I think it goes without saying that in this population, THC intoxication can be quite intense and overwhelming. There is also no evidence that these drivers had much — if any — familiarity with performing the skills asked of them while under the influence of cannabis. Finally, these subjects were average drivers and not highly skilled/trained athletes such as racecar drivers. These issues are important when trying to relate the effects on performance observed here to that which might be seen in trained athletes attempting to use cannabis as an ergogenic agent. Most athletes attempting to use cannabis in this fashion are likely to be regular or at least semi-regular users and as such are already familiar with its effects and, if attempting to use it ergogenically, would quickly become familiar with performing under these effects. Trained athletes, especially Olympic or professional level athletes, are by definition highly skilled and not just the average Jane who knows the rules of the game and plays with her friends. As such, when they compare to the population of drivers, they are the equivalent of a competitive race car driver.

An attempt was made to address at least one of these issues when the study was replicated. This time the researchers used participants who were all at least “occasional cannabis smokers” (13). It could therefore be argued that the subjects were reasonably familiar with the effects of cannabis and may have even driven under its influence in the past. This, however, only helps address some of the issues with the first study and does not resolve even those as signs of tolerance do not usually express in occasional smokers, which more often express signs of sensitization to the effects of cannabis especially in novel environments like the laboratory. Furthermore, both studies use oral and not intrapulmonary administration of THC. Most users of cannabis who have tried both routes of administration would agree that they produce discernibly different effects, one of which is a more prolonged and steady intoxication with the oral route while smoking peaks quickly and beginning to drop off within two hours. All these factors make it hard to equate such studies to the performance of highly skilled athletes evidencing signs of tolerance to the effects of cannabis, who are used to smoking small quantities before engaging in their chosen specialty.

A pilot study has attempted to address the issue of regular vs. novice or irregular use of cannabis but because of a sample size of two, it is of limited value at this time. However, the fact it utilized PET scans as part of the measure of performance both when the participants where sober and under the influence of THC makes the results interesting. When under the influence, the participants appeared to have higher metabolism compared to when sober in areas related to attention and motor coordination, and less activation in the motion traction parts of the visual cortex. These findings suggest that even in regular users, cannabis intoxication may negatively impact tasks that require coordinated movement, such as driving or sports (14). That said, the task was not one the subjects were highly experienced with or had experience with under the influence of cannabis.

Most of the previous issues, except for the high performance sports driver comparison, were reasonably effectively address finally by Ronen, et al. 2008. Ronen and colleagues mainly found that soon after smoking, cannabis appeared to impair driving abilities and increase the physical effort and discomfort involved in driving. This was accompanied by a tendency to compensate by slowing down compared to baseline scores. Compare this to a blood level of 0.05% alcohol, which was found to increase sleepiness while increasing speed over baseline scores. The subjects in this study smoked either 13mg or 17mg THC, were familiar with driving and the effects of cannabis, and they still showed signs of impairment (which they correctly adjusted for) in this complex behavior. That said, no impact on driving was observed 24 hours after the 17mg dose (15). So, based on these findings, our analogy can at least say that it is likely that for average, non-professional athletes who use cannabis on a semi regular to regular basis outside of doing their chosen sport, getting high shortly before participating would probably impair their performance. That said, give even one day since their last use and there should be no impact.

This still however leaves the question of the high performance drivers (no pun intended) experienced with the use of cannabis of which there are several (see Table 1). How would this group perform if they were given time to adjust to the testing environment (i.e. the driving simulator) and to the effects of cannabis in this environment? I would not be satisfied with this analogy for sports until about 15 sports drivers familiar with the effects of cannabis were given at least ten 30 to 60 minute training sessions on the simulator, five tests sober and five after smoking cannabis, followed by two testing days both sober and after smoking. It is suggested that only under these conditions would it be most likely to observe the ability of cannabis to facilitate getting “in the zone” during a measure of driving performance and that only this would make the analogy complete since facilitating psychological flow is the primary reason athletes would use cannabis ergogenically.

Another implication of this analogy is that perhaps Nick Diaz is special in the way he responds to cannabis because of his ADHD. This would definitely appear to be a possibility when one considers the case report of the young German man with ADHD who in the process of reapplying for his driver’s license was tested under the influence of rather high serum levels of cannabinoids and was found to be better than averagely fit to drive on several of the measures of performance taken and at least passing on all the others. It was suggested that cannabinoids were producing a beneficial effect on this individual’s ADHD symptoms and may actually be improving his performance over baseline (which was not taken because the subject was clearly in no state to drive) (16). If we apply this to our driving/sports analogy, we see that it is possible the same could be happening for Nick Diaz, even though it has been demonstrated he can win just fine while testing negative for cannabinoids. If this were the case, then he would be outside the norm and not be representative of the impact of cannabis use on athletes.

Chronic Intoxication in Experimental Animals

Some of the effects of cannabis intoxication believed to be important to performance in sports have been studies in rats, so it would be reasonable to ask for which effects are tolerance observed and for which is it absent. One effect of CB1 agonists, like THC, which repeatedly apparently fails to induce the development of tolerance is the acquisition and retrieval of spatial memory. Even after repeated daily exposure for two weeks, rats and mice both appear to express spatial memory deficits when tested under the influence of the drug (17, 18).

That said, other findings have called these findings into question. One measure of a drug’s rewarding properties is whether or not, and to what degree, it can produce preference for a drug-linked environment given a choice when sober. This is called the conditioned place preference paradigm. Most drugs of serious abuse (nicotine, caffeine, alcohol, cocaine and other stimulants, opiates, benzodiazepines and barbiturates) readily induce place preference in lab animals. The cannabinoids, on the other hand, appear to only do so when very specific conditions are met. Otherwise, THC and synthetic cannabinoids have been repeatedly shown to produce place aversion (19, 20). Furthermore, cannabinoid antagonism appears to induce place preference in these animals (19). This finding has implications for performance of spatial memory tasks in rodents suggesting that “distaste” for cannabinoid intoxication could be inhibiting performance as much as or more so than impairment of spatial memory as such (20). Even worse, such effects as place preference or aversion only grow stronger with repeat exposure, which would indeed give the impression of lack of tolerance to the supposed spatial memory impairment. Another study of especially long-term exposure (13 weeks) to high doses in rats, followed by seven weeks abstinence from the drug, found that not only did the THC-treated animals show no impairments compared to their untreated counterparts, but that those who had received the two highest doses exhibited less signs of anxiety and better complex maze performance (21). It appears if anything that long term exposure to THC improved sober spatial functioning in these animals.

Even though spatial memory issues observed in animals following cannabinoid intoxication are used to strengthen the arguments against the use of cannabinoids by athletes, the full picture makes it hard to tell what if any relevance these observations have to human athletes. Furthermore, tolerance is indeed observed to many of the adverse acute effects of cannabinoid intoxication in animals. For example, although acute intoxication inhibits both acquisition of new tasks and performance on acquired tasks, tolerance to these effects developed after chronic administration. Interestingly, if a low-dose cannabinoid antagonist was substituted for THC following repeat exposure to THC, the ability to acquire a new task was impaired (22). This suggests that the brain learns to compensate for the disruptive effects of cannabinoids on learning, possibly through adjustments in the tone of the endocannabinoid system, and that learning can be impaired by any change significantly deviating from that which this system is currently set to.

Another potentially beneficial effect has been observed in animals following administration of low-dose cannabinoid agonists. Moderate to high doses of cannabinoids were found to inhibit stimulus detection processes. However, low doses appear to facilitate stimulus detection (23). This suggests that not only can athletes develop tolerance to many of the adverse effects of acute cannabinoid intoxication but that a hit or two of cannabis might actually improve some parts of the athlete’s game, such as “keeping their eye on the ball.” It might be particularly interesting to study this question in cannabis smoking jugglers, of which there are many.

Measures of Performance in Regular Users

Although a consensus has not been reached, many studies have presented evidence suggesting intoxication-induced impairment even in long-term regular cannabis users. There is, however, general consensus on the acute effects. During acute intoxication, cannabis disrupts vigilance, ability to perform mental tasks, explicit and working memory, and one’s ability to correctly estimate intervals of either time or space. Negative reactions such as panic, random disconnected thoughts, hallucinations, delusions and other disturbing perceptual changes can also occur in some individuals (24). Although occasionally appearing at typical recreational doses, such responses occur more frequently with does significantly larger than typical for the individual in question (Interestingly, the WHO has suggested that at least synthetic THC be placed on Schedule IV of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Drugs, the lowest and least restrictive of this scheduling system (24).). It seems that, with rare exception, acute cannabis intoxication will result in impaired performance in sports.

So how does frequent intoxication compare to the acute intoxication? One of the first studies to really effectively address this question found that while mental processing speed was slower, accuracy in task performance was unaffected by the intoxication produced by smoking THC in regular users of cannabis (average: 24 joints a week) (25). This suggests that while processing speed for explicit tasks requiring executive functions may be somewhat impaired in regular cannabis smokers, they have found ways of compensating for many of the other effects, possibly at the cost of this reduction in processing speed. Another study found that in regular users smoking 13mg, THC produces no significant cognitive-motor skill or coordination impairment, and only a slight impairment to processing speed. On the other hand, the same users were significantly impaired by 17mg THC on measures taken. This is despite the fact that both doses were rated as pleasurable, with good drug effect and high (26). A year later, another study essentially confirmed this finding. Here it was demonstrated that even at the peak of effect, frequent uses showed no significant impairments other than a slight reduction in processing speed as evidenced by a slight increase in reaction time in the stop signal task. In contrast, the same dose significantly impaired performance of occasional users on all measures taken. This suggests that the performance of athletes who frequently use cannabis would not be particularly impaired by low doses of cannabis.

Where do the Athletes Stand?

There is little question where Nick Diaz stands. Cannabis helps him approach life more consistently, possibly even including his training, though this is not so clear. In the past, smoking the night before a fight has not appeared to affect his performance. However, Nick Diaz is just one of millions of athletes the world over. He is also not the first to come out publicly in support of cannabis. For example, Mark Stepnoski, five-time All-Pro center and member of two winning Dallas Cowboy Super Bowl championship teams, is a long time cannabis smoker who went on from football to take over as president of the Texas chapter of NORML. Although admitting to socially using cannabis periodically from high school through his career, Mark claims to have done his best to have kept his cannabis use and his athletic life separate. Although not providing much input on the effects of cannabis on performance, Mark is clearly no slouch and his story does not suggest that his cannabis use hurt his career in any discernable fashion (27).

On an administrative level, the UK’s Sports Minister, Richard Caborn, stated in 2006 that he felt the ban on cannabis should be lifted for the 2012 London Olympic Games, suggesting the real threat lay in the realm of ever evolving serious doping agents. Let the police focus on policing society and social drugs. He suggests, “[The World Anti-doping Authority is] not in the business of policing society. We are in the business of rooting out cheats in sports. That’s what WADA’s core function is about (28).” However this is of little consolation for those, like Canadian Olympic Snowboarder Ross Rebagliati, have already had their gold medals revoked due to testing positive for cannabis. Clearly Ross was not impaired by the significant level of cannabinoids in his bloodstream when he won that good medal. However, you never know, this might be just what multi-record breaking multi-gold medalist, Michael Phelps, was hoping to hear. Perhaps then he might grow some integrity, instead of caving and apologizing for something reasonably benign at the first sign of corporate sponsor pressure. Let your record speak for itself, Michael, it demands no apology.

In most cases, the portion of cannabis users inside any given sport is often significant and may in some cases even be a majority. Those cannabis users inside pro sports have often reported that cannabis use amongst their peers is common if not rampant. During an interview with the New York Post in 2001, basketball player Charles Oakley claimed that about 60% of his fellow NBA players use cannabis, which agrees with the findings of a 1997 poll which found between 60% and 70% of players at the time consumed cannabis. Indeed, NBA and NFL players get busted for cannabis possession or for testing positive for it on a regular basis and many of the highest performing NBA players are rumored to be regular users (29). One NFL player, Ricky Williams, has even retired rather than unnecessarily change his lifestyle for the game (30).

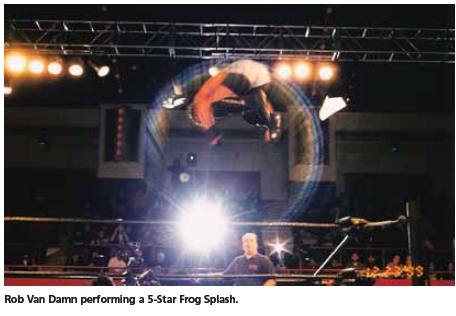

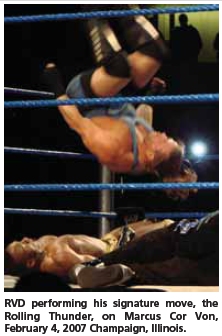

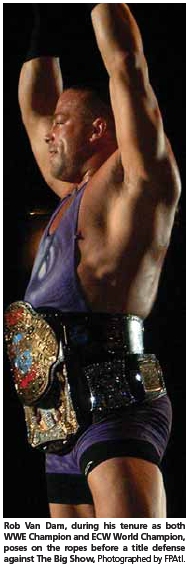

In a truly inspirational piece of work on the subject, semi-retired pro-wrestler and avid cannabis activist Rob Van Dam, not only suggested cannabis was quite common in his sport, telling stories of personal use with other wrestlers and pointing to numerous cannabis-related busts of pro-wrestlers, but suggested that it could provide performance enhancing effects “in athletic and contact sports (such as wrestling, power-lifting, football), co-ordination sports (snowboarding, surfing, basketball), and finesse sports (golf, bowling) (30).” His observations appear to be confirmed by Table 1, which lists a diverse variety of athletes caught “doping” with cannabinoids. Rob Van Dam is perhaps the most extreme pro-wrestler to date. Starting out at Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW) and eventually moving to World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) when the original ECW went under in 2001, Rob Van Dam has participated in over 1000 events. He is the only wrestler to have held both the ECW and the WWE championships at the same time (31). All together, he held 19 Championship belts, some multiple times, and received numerous other commendations throughout his primary wrestling career.

For those stuck on the fact that pro-wresting is a semi-scripted sport, to put it bluntly — some of that shit simply can’t be faked! He has also received numerous injuries over his career, ranging from concussions to broken limbs and eventually surgery on one of his knees (30). As he said in a 1999 interview with High Times when asked what it’s like to land on a concrete floor, “It feels exactly like what it looks like. When I jump over the top rope and land ten feet down on my head on the cement, it feels like I just landed on my head on cement (32).” Not wanting to impede his dream of pro-wresting, Rob did not even try cannabis until his 21st birthday, a year after he became a professional wrestler. He was at an event in Jamaica with other pro-wrestlers he had always looked up to and it was these fellow athletes who introduced him to cannabis. He has used cannabis regularly ever since, claiming to have frequently used cannabis at events, even once almost missing his cue while passing a joint with his peers. In other words, he performed his extreme death-defying feats exceptionally well, even when technically high (30).

When asked what it was like to perform after smoking a joint and if he had ever experienced what he felt were negative effects on his performance, Rob had this to share this with me:

“The effects of cannabis block stresses of the mind and body, and also seem to bring out a happy, positive emotion that can be referred to as ‘comfortable.’ Finding comfort while performing high pressure situations is extremely helpful. The pressures applied by the circumstances as well as by oneself to be at one’s very best in front of a live crowd of screaming fans makes most performers visibly nervous, often for hours before the event, gaining momentum as the moment approaches. To be able to walk through the curtains feeling fine and even looking forward to ‘doing your thing’ can turn an intense experience into a pleasurable one at times, and it shows in the performance.

I’ve found that agility and gracefulness are not affected, only attitude in a positive way. On the other hand, I do believe that a slight measure of respiratory stamina is sacrificed, meaning the performer may breath just a little bit harder when intoxicated — which is offset by being in great condition. If the competition is a breath holding contest or maybe even a long distance run, it is possible that a lot of toking could work against you, but I also believe that the amount of consumption is a huge factor at that point, meaning one or two tokes (prospectively) may benefit that same runner.”

In his article, Rob goes on to discuss how cannabis might facilitate performance in different sports. By far the most insightful of his observations, and one crucial to the development of the central thesis of this article, is that cannabis appears to facilitate the change in mental and physical state required to “get into the zone” (30). This observation is important because in it is the key to unlocking how cannabis can be ergogenic under the right circumstances. It is also one very familiar to the cannabis using population of jugglers such as myself but one which I had not personally put much thought into before.

Flow into the Zone

After reading Rob Van Dam’s comments on “the zone,” or psychological Flow as it is officially called, I was able to build a picture of what is going on in the brain during this process on a variety of measures and related these to how cannabis effects the same measures. In so doing, I came up with a testable theory for the most likely conditions under which ergogenic effects from cannabis might be observed experimentally, thereby proving what many athletes have been saying all along. I propose a theory of low-dose cannabis-induced ergogenesis, in the form of improved access to the state of flow, in highly skilled athletes evidencing signs of tolerance to the effects of regular cannabis use.

Psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi proposed the concept of “Flow,” deriving the name from the phrase “going with the flow.” Although he admits he is not the first to document this state, he may be the first to describe it in Western psychology. There are several features which commonly occur during the state of flow, not all of which need be present for the state to qualify. Wikipedia lists the nine features as (33):

“Clear goals (expectations and rules are discernible and goals are attainable and align appropriately with one’s skill set and abilities).

Concentrating and focusing, a high degree of concentration on a limited field of attention (a person engaged in the activity will have the opportunity to focus and to delve deeply into it).

A loss of the feeling of self-consciousness, the merging of action and awareness.

Distorted sense of time, one’s subjective experience of time is altered.

Direct and immediate feedback (successes and failures in the course of the activity are apparent, so that behavior can be adjusted as needed).

Balance between ability level and challenge (the activity is neither too easy nor too difficult).

A sense of personal control over the situation or activity.

The activity is intrinsically rewarding, so there is an effortlessness of action.

People become absorbed in their activity, and focus of awareness is narrowed down to the activity itself, action awareness merging (33).”

There are several situations in which flow is commonly experienced. Musicians often experience it, especially when performing improvisational solos. It may also be experienced during some forms of meditation. Modern video games are often designed around the concept so as to make for a full emersion experience; when playing, you lose awareness of time and to a great extent the rest of your inner and outer environment. It has also been suggested that runners in the depths of a “runner’s high” experience this state. The ability to enter and utilize this state is necessary for the mastery of such sports as tennis and golf. Professional racers have even described the experience of flow during particularly good races (33).

“When challenges and skills are simultaneously above average, a broadly positive experience emerges. Also vital to the flow state is a sense of control, which nevertheless seems simultaneously effortless and masterful. Control and concentration manifest with a transcendence of normal awareness; one aspect of this transcendence is the loss of self-consciousness (33).”

In some people, cannabis can produce flow-features 3, 4, 9 and possibly 8. This is the second suggestion that cannabis might facilitate entering the state of flow, the first coming from athletes stating so. Besides these psychological features of flow, there are also brainwaves and neural features which accompany it. Decreases in beta and increases in alpha, theta and sometimes even delta brainwaves are believed to be associated with the same situations as flow is associated with. This includes meditation (34), the runner’s high (35), golf (36) and group drumming (37). The use of cannabis also increases theta and alpha waves at the expense of beta waves. Even the relatively non-psychoactive cannabinoid, cannabidiol (CBD), on its own is capable of producing this effect (38). Acute administration of THC produces this effect on the brainwaves transiently (39) whereas heavy use for 15-24 years consecutively produces a constant increase in theta and alpha waves (40). This change in brain activity has been dubbed “transient hypofrontality” because of decreases on frontal lobe activity observed during activities such as endurance running, daydreaming, meditation and many forms of drug intoxication (41).

The neurocognitive basis for the transient hypofrontality observed during the experience of flow has been elucidated by Dietrich in 2004 (42). Cognitive theory has proposed separate but equal forms of memory/processes in the brain called the implicit or procedural memory and explicit or declarative memory. Explicit memory involves deliberate, conscious retrieval of learned information or previous experiences. The definition of implicit is a bit more elusive for some. Implicit memory involves things exemplified by the phrase “you never forget how to ride a bike.” The use of the implicitly learned memory “how to ride a bike” gets automatically accessed and utilized with no conscious effort on your part. An explicit process would be consciously working out how to read a new word whereas an implicit process would be the typical effortless reading you are non-consciously doing now (43). Not only do these two types of memory differ in function but also differ in which brain regions they utilize. Dietrich, 2004, used this framework to analyze flow and develop a very enlightening picture of the phenomenon. First he discussed neural structures associated with the two types of memory. Implicit memory is mostly supported by the basil ganglia whereas the frontal lobe and medial temporal structures underlie explicit memory. Where skill-based implicit memory is more efficient, explicit processes involve the executive functions associated with greater flexibility and gone awry allow us to over-think things. Usually explicit functions dominate conscious awareness and neurocognitive resources, however, during flow, these functions are suppressed and resources are diverted to the more efficient implicit processes that come to the forefront of awareness. This allows the most practiced skills to be put to use without any interference from the “over-thinking” explicit processes (42). The experience of flow thus by definition requires a state of transient hypofrontality very similar to that produced by cannabis.

In diverting resources away from the forebrain and its related executive processes to the areas of the brain associated with coordinated movement such as the visual cortex and motor cortex, this transient hypofrontality is produced by exercise and is likely responsible for much of the cognitive and emotional benefits observed after exercise (44). Similar changes in neural activity have also been observed in jazz improvisation using functional magnetic resonance imaging (45, 46, 47). Some athletes have suggested that the easier it is to reach this state and the faster one reaches it, the more benefit one gains from the exercise and that cannabis provides just such facilitation. As Rob Van Dam might say, if you are not comfortable, you are just not going to get in the zone. Cannabis provides a comfortable state of mind. Considering the historically high frequency of cannabis use among jazz musicians, one must wonder if they feel similarly.

As it turns out, cannabis too produces this state of hypofrontality (48), transiently at first (39) and then pervasively with heavy daily use over a period of decades (40). Cannabis suppresses the explicit memory and related functions while leaving implicit memory and working memory functions untouched. Indicative of the implicit/explicit efficiency/flexibility trade off, THC can produce a speed/accuracy trade off (48).

Conclusion

These findings help elucidate the effects of cannabis and THC which could prove useful in inducing flow and thereby improve performance. The use of low doses of cannabis in regular users may improve stimulus detection and visual tracking (23), suppress the executive functions in the forebrain, and allow well-learned skills in the implicit memory to readily come to the forefront. This facilitation of flow would be most likely to occur in regular users of cannabis and when the difficulty of the activity at hand was well-matched to the skill level of the person performing it. In the case of low-dose cannabis combined with exercise and sports, there may even be a degree of hypofrontality synergism produced. It is likely that these benefits would be lost after administration of moderate and strong doses and therefore should be avoided in combination with such activities. It is suggested that the less of a skill base an athlete already possessed, the less benefit cannabis could provide. For some activities, cannabis could even be an impediment until the skill as been mastered.

The theory I have proposed here is based on anecdotal and experimental evidence. The theory itself has not been directly tested to date in the laboratory but is clearly worth investigating. Future research should focus on the highly skilled “artisans” of any field, in particular the regular cannabis users among them, while they are under the influence of small doses of THC or cannabis. It may also be useful to rule out the amplified effects of cannabis intoxication in a novel environment by providing at least two training sessions in the experimental environment under the influence of cannabinoids. A couple fields which might be particularly worth investigating are high performance drivers, skilled jugglers capable of improvisational juggling (i.e., not following a single pattern or routine), and video game savants.

Would this potentially ergogenic effect from cannabis facilitated flow be considered cheating by the various sports authorities? Or would UK’s Sports Minister, Richard Caborn, withdraw his request that cannabis be removed from the list of substances banned from 2012 Olympics if he suspected it? Perhaps yes, but it is also possible that such an effect would be determined to be inconsequential as hints to its existence have often been scientifically dismissed in the past. In the meantime, it is likely that those athletes in the know like Ron Van Dam and Nick Diaz will simply continue to do what they know works while outperforming their peers, setting records, winning championships and earning gold medals.

References

Pugmire, L. MMA fighter Nick Diaz says smoking marijuana is part of his plan. Los Angeles Times, 2009 Apr 9.

Vandermeer, J. Pot Smoking Athlete’s Comments Cause Controversy. Cannabis Culture, 2009 Apr 24. HYPERLINK “http://www.cannabisculture.com/v2/content/pot-smoking-athletes-comments-cause-controversy”www.cannabisculture.com/v2/content/pot-smoking-athletes-comments-cause-controversy (Accessed 5/20/2009).

Hockensmith, R. MMA Submission: Nick Diaz’s Life Choices. Yea. That stuff. But is it a distraction? ESPN: The Magazine, 2009 Apr 10.

Nick Diaz. Wikipedia. HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nick_Diaz”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nick_Diaz (Accessed 5/20/2009).

Frank Shamrock: MMA Record. Wikipedia HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Shamrock” \l “MMA_record”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Shamrock#MMA_record (Accessed 5/20/2009).

Randy Couture: Mixed Martial Arts Record. Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randy_Couture#Mixed_Martial_Arts_record (Accessed 5/20/2009).

Ewing, BT. High school athletes and marijuana use. Journal of Drug Education, 1998; 28 (2): 147-57.

Lorente, FO, Peretti-Watel, P and Grelot, L. Cannabis use to enhance sportive and non-sportive performances among French sport students. Addict Behaviors, 2005 Aug; 30 (7): 1382-91.

Bahrke, MS and Yesalis, C. Performance-enhancing substances in sport and exercise. Human Kinetics Publishers; 1 ed, 2002.

Campos, DR, Yonamine, M and de Moraes Moreau, RL. Marijuana as doping in sports. Sports Medicine, 2003; 33 (6): 395-9.

Saugy, M, Avois, L, Saudan, C, Robinson, N, Giroud, C, Mangin, P, and Dvorak, J. Cannabis and sport. British Journal Sports Medicine, 2006 Jul; 40 Suppl 1: i13-5.

Ménétrey, A, Augsburger, M, Favrat, B, Pin, MA, Rothuizen, LE, Appenzeller, M, Buclin, T, Mangin, P, and Giroud, C. Assessment of driving capability through the use of clinical and psychomotor tests in relation to blood cannabinoids levels following oral administration of 20 mg dronabinol or of a cannabis decoction made with 20 or 60 mg Delta9-THC. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 2005 Jul-Aug; 29 (5): 327-38.

Giroud, C, Augsburger, M, Favrat, B, Menetrey, A, Pin, MA, Rothuizen, LE, Appenzeller, M, Buclin, T, Mathieu, S, Castella, V, Hazekamp, A, and Mangin, P. [Effects of oral cannabis and dronabinol on driving capacity]. Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises, 2006 May; 64 (3): 161-72.

Weinstein, A, Brickner, O, Lerman, H, Greemland, M, Bloch, M, Lester, H, Chisin, R, Mechoulam, R, Bar-Hamburger, R, Freedman, N, and Even-Sapir, E. Brain imaging study of the acute effects of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) on attention and motor coordination in regular users of marijuana. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2008 Jan; 196 (1): 119-31.

Ronen, A, Gershon, P, Drobiner, H, Rabinovich, A, Bar-Hamburger, R, Mechoulam, R, Cassuto, Y, and Shinar, D. Effects of THC on driving performance, physiological state and subjective feelings relative to alcohol. Accident; Analysis and Prevention, 2008 May; 40 (3): 926-34.

Strohbeck-Kühner, P, Skopp, G and Mattern, R. [Fitness to drive in spite (because) of THC]. Archiv für Kriminologie, 2007 Jul-Aug; 220 (1-2): 11-9.

Nava, F, Carta, G, Colombo, G, and Gessa, GL. Effects of chronic Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol treatment on hippocampal extracellular acetylcholine concentration and alternation performance in the T-maze. Neuropharmacology, 2001 Sep; 41 (3): 392-9.

Boucher, AA, Vivier, L, Metna-Laurent, M, Brayda-Bruno, L, Mons, N, Arnold, JC, and Micheau, J. Chronic treatment with Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol impairs spatial memory and reduces zif268 expression in the mouse forebrain. Behavioral Pharmacology, 2009 Feb; 20 (1): 45-55.

Cheer, JF, Kendall, DA, and Marsden, CA. Cannabinoid receptors and reward in the rat: a conditioned place preference study. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2000 Jul; 151 (1): 25-30.

Robinson, L, Hinder, L, Pertwee, RG, and Riedel, G. Effects of delta9-THC and WIN-55,212-2 on place preference in the water maze in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2003 Feb; 166 (1): 40-50.

Holson, RR, Ali, SF, Scallet, AC, Slikker, W Jr, and Paule, MG. Benzodiazepine-like behavioral effects following withdrawal from chronic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol administration in rats. Neurotoxicology, 1989 Fall; 10 (3): 605-19.

Delatte, MS, Winsauer, PJ, and Moerschbaecher, JM. Tolerance to the disruptive effects of Delta(9)-THC on learning in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2002 Dec; 74 (1): 129-40.

McLaughlin, PJ, Brown, CM, Winston, KM, Thakur, G, Lu, D, Makriyannis, A, and Salamone, JD. The novel cannabinoid agonist AM 411 produces a biphasic effect on accuracy in a visual target detection task in rats. Behavioral Pharmacology, 2005 Sep; 16 (5-6): 477-86.

Carlini, EA. The good and the bad effects of (-) trans-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Delta 9-THC) on humans. Toxicon., 2004 Sep 15; 44 (4): 461-7.

Vadhan, NP, Hart, CL, van Gorp, WG, Gunderson, EW, Haney, M, and Foltin, RW. Acute effects of smoked marijuana on decision making, as assessed by a modified gambling task, in experienced marijuana users. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 2007 May; 29 (4): 357-64.

Weinstein, A, Brickner O, Lerman, H, Greemland, M, Bloch, M, Lester, H, Chisin, R, Sarne, Y, Mechoulam, R, Bar-Hamburger, R, Freedman, N, and Even-Sapir, E. A study investigating the acute dose-response effects of 13 mg and 17 mg Delta 9- tetrahydrocannabinol on cognitive-motor skills, subjective and autonomic measures in regular users of marijuana. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 2008 Jun; 22 (4): 441-51.

Gorman, P. HIGH TIMES INTERVIEW: Mark Stepnoski. High Times, 2009 Apr. HYPERLINK “http://hightimes.com/news/ht_admin/231″http://hightimes.com/news/ht_admin/231 (Accessed 5/23/2009).

Allow Athletes to use Cannabis, Says Sports Minister. London Evening Standard, 2006 Dec 12. HYPERLINK “http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/news/article-23378010-details/Allow+athletes+to+use+cannabis,+says+sports+minister/article.do”http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/news/article-23378010-details/Allow+athletes+to+use+cannabis,+says+sports+minister/article.do (Accessed 5/23/2009).

Sind, B. Stoned Sportsmen. Cannabis Culture Magazine, 2001 June. HYPERLINK “http://www.cannabisculture.com/articles/1951.html”http://www.cannabisculture.com/articles/1951.html (Accessed 5/23/2009).

Van Dam, R. Weed, Wrestling, and Athletic Enhancement. Cannabis Culture Magazine, 2008 Sep. HYPERLINK “http://www.cannabisculture.com/v2/content/weed-wrestling-and-athletic-enhancement”http://www.cannabisculture.com/v2/content/weed-wrestling-and-athletic-enhancement (Accessed 5/23/2009).

Rob Van Dam. Wikipedia. HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rob_Van_Dam”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rob_Van_Dam (Accessed 5/23/2009).

Holmstrom, J. Rob Van Dam ‘420’: I Am The Fucking Show. High Times Archive, 1999 March. HYPERLINK “http://hightimes.com/entertainment/agrossmann/2690″http://hightimes.com/entertainment/agrossmann/2690 (Accessed 5/23/2009).

Flow (psychology). Wikipedia. HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_(psychology)” \l “cite_note-0″http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_(psychology)#cite_note-0 (Accessed 5/24/2009).

Brainwaves: Normal Activity: Wave Patterns. Wikipedia. HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brainwaves” \l “Wave_patterns”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brainwaves#Wave_patterns (Accessed 5/24/2009).

Brain Wave States & How To Access Them. Synthesis Learning 2005-2008. HYPERLINK “http://synthesislearning.com/article/brwav.htm”http://synthesislearning.com/article/brwav.htm (Accessed 5/24/2009).

Baumeister, J, Reinecke, K, Liesen, H, and Weiss, M. Cortical activity of skilled performance in a complex sports related motor task. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2008 Nov; 104 (4): 625-31.

Winkelman, M. Complementary therapy for addiction: “drumming out drugs”. American Journal of Public Health, 2003 Apr; 93 (4): 647-51.

Murillo-Rodríguez, E, Millán-Aldaco, D, Palomero-Rivero, M, Mechoulam, R, and Drucker-Colín, R. The nonpsychoactive Cannabis constituent cannabidiol is a wake-inducing agent. Behavioral Neuroscience, 2008 Dec; 122 (6): 1378-82.

Struve, FA, Manno, BR, Kemp, P, Patrick, G, and Manno, JE. Acute marihuana (THC) exposure produces a “transient” topographic quantitative EEG profile identical to the “persistent” profile seen in chronic heavy users. Clinical Electroencephalography, 2003 Apr; 34 (2): 75-83.

Struve, FA, Patrick, G, Straumanis, JJ, Fitz-Gerald, MJ, and Manno, J. Possible EEG sequelae of very long duration marihuana use: pilot findings from topographic quantitative EEG analyses of subjects with 15 to 24 years of cumulative daily exposure to THC. Clinical Electroencephalography, 1998 Jan; 29 (1): 31-6.

Dietrich, A. Functional neuroanatomy of altered states of consciousness: the transient hypofrontality hypothesis. Consciousness and Cognition, 2003 Jun; 12 (2): 231-56.

Dietrich, A. Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the experience of flow. Consciousness and Cognition, 2004 Dec; 13 (4): 746-61.

Explicit Memory. Wikipedia. HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Explicit_memory”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Explicit_memory (Accessed 5/24/2009).

Dietrich, A. Transient hypofrontality as a mechanism for the psychological effects of exercise. Psychiatry Research, 2006 Nov 29; 145 (1): 79-83.

Limb, CJ and Braun, AR. Neural substrates of spontaneous musical performance: an FMRI study of jazz improvisation. PLoS ONE, 2008 Feb 27; 3 (2): e1679.

Bengtsson, SL, Csíkszentmihályi, M and Ullén, F. Cortical regions involved in the generation of musical structures during improvisation in pianists. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 2007 May; 19 (5): 830-42.

Berkowitz, AL and Ansari, D. Generation of novel motor sequences: the neural correlates of musical improvisation. NeuroImage, 2008 Jun; 41 (2): 535-43.

Curran, HV, Brignell, C, Fletcher, S, Middleton, P, and Henry, J. Cognitive and subjective dose-response effects of acute oral Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in infrequent cannabis users. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2002 Oct; 164 (1): 61-70.

Contains Introduction Letter, Rate Card & Insertion Order Form

Contains Introduction Letter, Rate Card & Insertion Order Form

Brilliant read!

Very nice site!

treatingyourself.com has become a favorite sunday point for me

You have done it again! Amazing article!

Incredibly awesome article. Truely.